Ivor Gurney and My Trousers Part Two

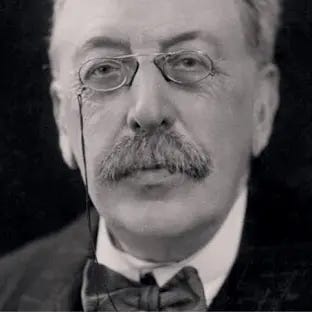

Ivor Gurney at the Royal College of Music

I first wrote about Ivor Gurney on Open Salon many years ago. I received a kind comment from Pamela Blevins in North Carolina. She knows much more about Gurney than I ever could but was charitable about my efforts. I have since read her book, Ivor Gurney and Marion Scott: Song of Pain and Beauty, which I heartily recommend. I have a handsome hardback edition, but it is also available on Kindle.

In Part One, I described how Ivor Gurney, coming from a modest background in Gloucester, won a place in the Gloucester Cathedral Choir in 1900. In 1911, he took up an open scholarship in composition at the Royal College of Music. His examiners were a formidable team of British composers: Sir Hubert Parry (best known for his setting of Blake’s Jerusalem); Sir Charles Stanford (an Irish composer and respected teacher, long resident and influential in England) ; Dr Walford Davies and Dr Charles Wood.

At the RCM, Gurney met his lifelong friend and supporter, Marion Scott. She was thirteen years older than he was and had trained as a violinist at the RCM. She now edited the college magazine. She described her first sighting of him when he was wearing a thick Severn pilot’s coat. “But what struck me more was the look of latent force in him, the fine head with its profusion of light brown hair (not too well brushed!) … ‘This,’ I said to myself, ‘must be the new composition scholar from Gloucester whom they call Schubert’.”

He had a great deal of charm, good looks, talent and intelligence and made many friends. He attended concerts, socialised, even became a member of the elite Beloved Vagabonds Club, which met at Holland Park to perform music.

Sir Charles Stanford was somewhat authoritarian, preferring order to chaos, and found Gurney’s manuscripts tended to the chaotic. Herbert Howells recalled an occasion when Stanford made some swift alterations in pencil and said: “There, me boy! That puts it right”. Gurney responded, “Well, Sir Charles, I see you’ve jiggered the whole show.” Stanford threw him out but turned to Howells, chuckled, and said, “You know, I love him more each time.” Stanford, in later years, declared that of all those he taught – Vaughan Williams, Ireland, and Bliss- Gurney was, potentially, “the biggest man of them all, but he was the least teachable.”

Gurney’s earliest compositions date from 1904, but the first songs of any consequence are dated November 1907. In 1908, the distinguished classicist and poet, AE Housman (subject of Tom Stoppard’s 1997 play The Invention of Love) wrote to his publisher about giving permission for a Gurney setting of Housman’s poems. “Mr IB Gurney (who resides in Gloucester Cathedral along with St Peter and Almighty God) must not print the words of my poems in full on concert programmes (a course which I am sure his fellow lodgers would disapprove of) but he is quite welcome to set them to music, and to have them sung, and to print their titles on programmes when they are sung.” In 1913, Gurney wrote settings of five Elizabethan lyrics – the “Elizas”.

Poetry

Gurney started writing poetry in 1913. A collection called Severn and Somme was published in 1917. In 1919, another collection, War’s Embers was published. Those were the only two books of poetry published in his lifetime. JC Squire worked hard on his behalf and published individual poems frequently in his London Mercury.

Squire commented: “It will all come out one day, I suppose. But the best in the arts still has the old struggle”. His poems frequently appeared in anthologies and the heavy-hitters in the poetry world like Auden and Larkin praised him. Another poet, Edmund Blunden, brought out a selection of Gurney’s poems in 1954, which had little impact.

Leonard Clark edited another selection in 1973, which caused few ripples. Michael Hurd’s biography in 1978 stressed the quality of Gurney’s poetry and provided many examples.

In 1982, poet PJ Kavanagh published The Collected Poems of Ivor Gurney, which showed the full range of his achievement and encouraged further re-issues. In 1996, Everyman’s Poetry published a selection edited by George Walter of Sussex University. Walter points out in his introduction that Gurney cannot easily be categorised as a war poet, a “mad” poet or even a pastoral poet. “Ultimately his poems have less to do with their ostensible subjects than with his own awareness of them as spiritual revelations.” His subjectivity allows him to avoid vague generalizations about pastoral subjects.

Gurney is fascinated by the urban and the man-made. He writes about impermanence in the natural landscape and, in poems like “Time to Come”, (which I quoted in Part One) writes about how the development of new housing in Gloucester affects the shape of the city and the landscape in which it sits. Google Longford, the district in Gloucester where Gurney lived with his aunt and did farm work, and all you get is information about house prices and new developments in locations with neologisms for names, names that did not exist when I was a child walking those fields. My junior school used Plock Court at Longford as a sports ground. It was a miracle that we did not get tetanus because cow shit carpeted the field.

Longford Dawns

Of course not all watchers of the dawn

See Severn mists like forced-march mist withdrawn;

London has darkness changing into light

With just one quarter-hour of any weight.

Casual and common is the wonder grown –

Time’s a duty to lift light’s curtain up and down.

But here Time is caught up clear in Eternity,

And draws as breathless life as you or me.

War

In 1915, Ivor Gurney joined the Fifth Gloucester Reserve Battalion and saw active service on the Western Front between June 1916 and September 1917. On Gurney’s departure for the Somme, Herbert Howells dedicated his Piano Quartet in A minor: ‘To the Hill at Chosen and Ivor Gurney who knows it’. Chosen Hill in Gloucestershire had been a favourite walking place for the two men. I used to walk from my home to the top of Chosen Hill and look at the city spread below me or sit in quiet contemplation in the church at top of the hill. Today one cannot take the same route because motorways, bypasses, and industrial estates dominate the landscape.

Most critics seem to agree that Gurney is not a war poet like Owen, Rosenberg or Sassoon. However, in the trenches, he began writing poetry prolifically. On April 6, 1917, he was shot in the upper arm.

Pain

Pain, pain continual: pain unending:

Hard even to the roughest, but to those

Hungry for beauty…Not the wisest knows,

Nor most pitiful-hearted, what the wending

Of one hour’s way meant. Grey monotony lending

Weight to the grey skies, grey mud where goes

An army of grey bedrenched scarecrows in rows

Careless at last of cruellest Fate-sending.

Seeing the pitiful eyes of men foredone,

Or horses shot, too tired merely to stir,

Dying in shell-holes both, slain by the mud.

Men broken, shrieking even to hear a gun-

Till pain grinds down, or lethargy numbs her,

The amazed heart cries angrily out on God.

He managed to write five songs in the trenches and get them published. The songs were about a longing for peace and security and a concern with the nature of death. “By a Bierside” was a setting of a poem by John Masefield; “In Flanders” is a setting of a poem by his friend FW Harvey.

Life in the Trenches

It would be easy to surmise that the horrors Gurney witnessed in wartime contributed to his mental collapse. Strangely, war brought him a kind of peace, Gurney seemed, to some extent, to enjoy the camaraderie of the trenches. “The life is as grey as it sounds, but one manages to hang on to life by watching the absolute unquenchability of the cheerier spirits – wonderful people some of them; after all, it is better to be depressed with reason than without. When confronted with a difficult proposition the British soldier emits (rather like the cuttle fish) a black appalling cloud of profanity; then does the job.”

According to Michael Hurd, Gurney was able to write calm letters home because he had found a kind of inner peace through being part of the war. Being an ordinary private meant he was a disposable item whose path was marked out for him without him having to make decisions. “Caught up in a loving comradeship wherein all suffered equally and endured, he felt perhaps for the first time in his life a sense of security – a sense that he was no longer the odd man out, and that he had found the family he had always been looking for.”

Blevins:"… and in the process had proved himself to be a competent, dependable soldier. He had discovered his poetic voice and turned war into art. He had published a successful volume of poetry and was working on another collection. He had composed five significant songs in France, three of which had been performed in London. He had fallen in love, and, for a time, he managed to find some respite from the mental anguish that had tormented him before the war."

"The base reality was that Ivor Gurney, the sensitive and gentle poet-composer, had killed other men, scavenged their rotting mutilated bodies, stolen from them without a pang of guilt and then expressed regret that he was not able to steal more. Men took what they could use and carry – food, revolvers, watches, rings, badges, compasses, books, papers. Ivor confided in Marion that after one battle he had spent an hour taking tea and sugar from dead men. He called this activity ‘salvaging’. ‘O the souvenirs I might have had! But only officers have any real good chance of souvenirs, since only they can get them off’, he wrote, adding that officers could make themselves ‘rich with booty’. But low-ranking combat soldiers like Ivor who ‘could not carry [their plunder] very well and had no place to store things and hardly a leave’ often left a scene empty-handed."

He did witness horrors. “The front-line trenches of both sides were very close to one another in places, so close in fact that a bomb could easily be thrown from one to the other, and No Man’s Land was littered with the dead bodies of men who had been scythed down by machine-gun fire in the last attack… The cemetery at Richebourg was an eerie spot; it had been completely churned up by shell fire: tombs torn open to reveal skeletons that had lain there for years. The crucifix, as was so often the case, remained standing.”

During the Passchendaele offensive of 1917, he was gassed and invalided home. He returned to Barton Street, Gloucester and worked in a munitions factory until Armistice Day (a week after Wilfred Owen was killed). In 1919, he returned to the Royal College of Music and was taught composition by Ralph Vaughan Williams. He took a post as organist at Christ Church, High Wycombe and began to move in London literary circles.

He suffered a severe breakdown in 1918. He claimed to have spoken to the spirit of Beethoven. By 1921, his life had become unsettled. He had songs and preludes published but formally left the Royal College of Music and went to live with his aunt in Longford and did farm work. He went back and forth from Gloucester to London and spent a week as a cinema pianist in Cornwall. In 1922, his third collection of poems was rejected. He lost three farm jobs in a month and got a job at Gloucester tax office, which lasted only 12 weeks because he proved incapable of performing even the most menial tasks.

Ivor’s brother, Ronald, had recently got married and Ivor went to live with them at their home in Worcester Street, Gloucester. Ivor was not an easy tenant. He shut himself up in the front room and shouted at Ronald and Ethel to keep away. He complained that ‘electrical tricks’ were being played on him and sat with a cushion on his head to prevent the electric waves from the radio getting into his brain.

Ivor made several suicide attempts and was certified insane by Dr. Soutar and Dr. Terry on 28 September, 1922. He was committed to a private mental hospital called Barnwood House. He was then moved to Stone House hospital at Dartford, Kent. Marion Scott visited him frequently and took him on outings with an attendant. She took him to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Old Vic. She also worked hard to get his poems and songs published. He produced a prolific output of poems but the songs came less readily. His mental condition continued to deteriorate. By 1926, he was severely deluded believing himself to be Beethoven, Haydn, Shakespeare and Hillaire Belloc among others. He became physically hostile to staff and patients.

Between 1913 and 1926, Ivor Gurney wrote about 900 poems. At a conservative estimate, despite his mental illness and incarceration, 300 of these were viable works, many of the highest quality. Hundreds of Gurney’s poems remain unpublished. Tim Kendall of Exeter University, together with Gurney expert, baritone Philip Lancaster, have been working on a three-volume variorum edition of Gurney’s complete poetry, for Oxford University Press. Volume One appeared in 2020 and will set you back £152.50.

As well as writing powerful poems about the war and about the natural landscape, Gurney had a quality of modernity through unsentimental observation transmuted into poetry by force of concentration. As George Walter writes: “His perception of the landscape, both urban and rural, is coloured by historical survival, and history is for Gurney a human experience: the ploughing up of a Roman coin makes him think not of empires or dynasties but of ‘some hurt centurion’ who lived in the land of the past.”

While in the trenches, Gurney dreamed about his beloved Gloucestershire. In the asylum, he was again deprived of it. Helen Thomas, the widow of the poet Edward Thomas, who had died in the war, visited him there. In 1960, she recalled those visits. On one visit, she took Edward’s ordinance survey maps of Gloucestershire and traced their fingers over the routes Edward had walked and Ivor loved so well. “He spent that hour in re-visiting his beloved home, in spotting a village or a track, a hill or a wood and seeing it all in his mind’s eye, a mental vision sharper and more actual for his heightened intensity. For he had Edward as his companion in this strange perambulation; and he was utterly happy, and without being over-excited.”

Helen Thomas wrote: “Ivor Gurney longed more than anything else to go back to his beloved Gloucestershire, but this was not allowed for fear he should try to take his own life. I said ‘But surely it would be more humane to let him go there even if it meant no more than one hour of happiness before he killed himself.’ But the authorities could not look at it in that way.”

They have left me little indeed

They have left me little indeed, how shall I best keep

Memory from sliding content down to drugged sleep?

But my blood in its colour even is known fighter-

If I were hero for such things here I would make wars

As love for dead things trodden under January stars.

Or the gold trefoil itself spending in careless places

Tiny graces like music’s for its past exquisitenesses.

Why war for huge Domains of the planet’s heights or plains.

(Little they leave me.) It is a dream, hardly my heart dares

Tremble for glad leaf-drifts thundering under January’s stars.

Thanks for restacking Peter.

Fascinating!